Essence-Based Interpretation

1. Introduction

I’ve put a lot of effort into writing good code. In pursuit of good code, I’ve studied refactoring, design patterns, various architectures, and development methods. Even when my code was working well, I often spent considerable time deliberating over a better structure or naming.

Nevertheless, I sometimes couldn’t find a definitive answer when it came time to choose between different approaches. One day I’d implement it one way, the next day another way, and this went on for a long time. Both methods had clear pros and cons, so whichever approach I chose, there was a sense of regret. Here, “method” could refer to a design pattern or simply the name of a function or variable.

At that point, I thought I had a certain level of competency as a developer, but these decision-making dilemmas didn’t seem like they would ever go away, no matter how much experience or effort I accumulated. I even considered the possibility that there was no single correct answer, that it all depended on personal preference—like an art form. Perhaps it was a sort of defense mechanism, similar to how some developers who don’t fully understand design patterns dismiss them as useless in the real world.

Then I suddenly realized what I had been missing. Let’s look at a few examples and figure out what that was.

2. Implementing Directional Keys

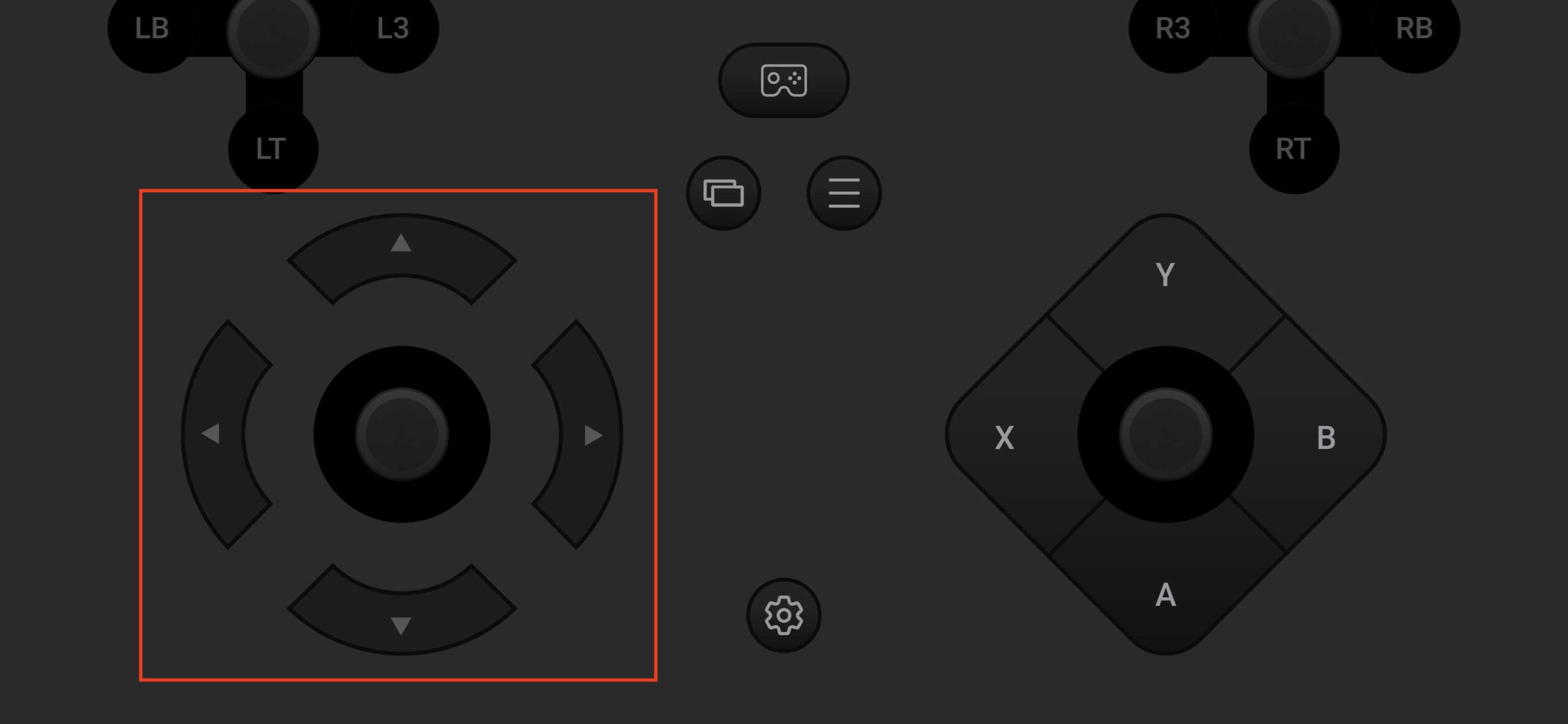

We need to provide a directional keypad for users where they can choose “Up/Down/Left/Right.” These four arrow icons look identical but point in different directions. There are two ways to implement this directional keypad.

Figure 2-1. A gamepad with identical-looking directional keys

2.1. Method #1 – Reusing one image with rotation

Method #1 uses a single arrow image (arrow.png) that is rotated to point in the different directions. Since the arrow shape is identical, it can be done easily.

This approach has the advantage of using less storage space. However, the downside is that the code readability can be relatively lower.

<Image src="arrow.png" rotate="0" />

<Image src="arrow.png" rotate="180" />

<Image src="arrow.png" rotate="-90" />

<Image src="arrow.png" rotate="90" />

Figure 2-2. A directional key implemented by rotating a single image

2.2. Method #2 – Using four separate images

Method #2 uses four separate images for up, down, left, and right.

The downside is that you have to manage more image resources, and the storage space usage also increases. On the other hand, the readability of the code is relatively better.

<Image src="up.png" />

<Image src="down.png" />

<Image src="let.png" />

<Image src="right.png" />

Figure 2-3. A directional key implemented with four images for up/down/left/right

2.3. Which method is correct?

Which one is correct? Or is there even a “right” or “wrong” choice here? Is it just a matter of personal philosophy? If you pursue efficiency, then Method #1 is for you, but if you want more readable code, you’d pick Method #2.

Is readable code correct? Or is performance-efficient code correct? In the past, performance efficiency might have been the priority, but in modern times where hardware performance is sufficient, readability often takes precedence. Should we then just choose the path of readability?

Many thoughts may come to mind, but the first thing to consider is the meaning of the arrow itself. If the arrow is something like Figure 2-4, indicating a specific object, then implementing it by rotating a single arrow image (like Method #1) makes sense.

Figure 2-4. Arrows used to point to something

But the user might have had in mind a directional keypad like Figure 2-5, the set of four arrow keys in the corner of a keyboard. In that case, four separate images (like Method #2) correspond more closely to what the user expects.

Figure 2-5. A directional key with four distinct arrow shapes

You might think there’s no big difference since the final result the user sees is the same, regardless of which method you choose. But what happens if you ignore the user’s perspective and only focus on implementation convenience?

The user might assume that changing the shape of the arrow keys is easy at any time, because they believe the keypad is made up of four separate images. Rotating a single image for performance optimization is purely a developer’s concern. Then one day, the user might ask you to change the directional keys to look like Figure 2-4. They’d think it’s just a simple image replacement, but for the developer, it becomes a major task that may require changing the entire approach.

The fact that the arrows happened to look the same initially is simply a coincidence. If you reflect that coincidence in the code, you drift further from the user’s thoughts and expectations. In other words, if you ignore the user’s intent and pursue only implementation convenience, maintenance becomes increasingly difficult.

2.4. The difficulty of interpretation

One reason it can be tough to discern the essence of a requirement is that some obvious information gets omitted.

When the user mentioned the need for “directional keys,” they probably didn’t explicitly say “the four arrow keys on a keyboard.” From the user’s standpoint, “directional keys” simply implies those keyboard arrows in the corner.

From a developer’s standpoint, though, if the requirement doesn’t detail that specific keyboard arrow concept, there’s more to ponder about how to implement it.

That’s where interpretation gets tricky: the parts that seem obvious and thus remain unspecified still have to be filled in by the developer. And to fill in those blanks, the developer must consider all the reasons and processes behind the requirement, which demands a wealth of experience and insight.

What if you still can’t pinpoint the user’s exact intent in this scenario? Or you can’t predict how it might change?

You could do something like the following—define Up, Down, Left, Right classes—so that no matter how the requirement for the arrows changes, it has minimal impact on the rest of the code.

<script>>

const Up = () => <Image src="arrow.png" rotate="0" />

const Down = () => <Image src="arrow.png" rotate="180" />

const Left = () => <Image src="arrow.png" rotate="-90" />

const Right = () => <Image src="arrow.png" rotate="90" />

</script>

<body>

<Up />

<Down />

<Left />

<Right />

</body>

3. Shallow Routing vs. Nested Routing in REST APIs

Figure 3-1 is a sequence diagram of how a user selects a movie, theater, and date/time in a movie ticketing system. How should we design the routing for a REST API in this situation?

Figure 3-1

3.1. Shallow Routing

If we design the REST API in the Shallow Routing style, it might look like this:

# Request list of showing movies

/movies?status=showing

# Request list of theaters

/theaters?movieId={movidId}

# Request list of show dates

/showdates?movieId={movieId}&theaterId={theaterId}

Shallow Routing lets you manage each resource independently, so it’s highly extensible. However, because it doesn’t clearly express relationships between resources, it can be challenging to represent complex hierarchical data.

3.2. Nested Routing

If we design the REST API in the Nested Routing style, it might look like this:

# Request list of showing movies

/showing/movies

# Request list of theaters

/showing/movies/{movieId}/theaters

# Request list of show dates

/showing/movies/{movieId}/theaters/{theaterId}/showdates

Nested Routing clearly represents the relationships between resources in the URL itself, making it suitable for complex resource structures. However, if the nested resource structure changes, the URL must also change, so it can be less flexible.

3.3. Which method is correct?

We briefly looked at the pros and cons of the two routing methods. So how do you choose between the flexibility of Shallow Routing and the clarity of Nested Routing?

It depends on which design more closely reflects the conceptual perspective of the movie ticketing process.

From that angle, Nested Routing reflects the ticket purchase process directly. Just as you have to select a movie before you can choose a theater, in Nested Routing, you cannot specify a theater without specifying a movie. In other words, the Nested Routing REST API mirrors the ticket purchase process. You might not even need separate documentation for it—it’s that intuitive.

You often see debates about which is better: Shallow Routing or Nested Routing. Such debates can be endless. What’s important is which design more accurately reflects the requirements. If you approach it purely from a technical standpoint, where there’s no single right answer, the debate never ends.

If you’ve been agonizing for a while and still see no solution, perhaps the answer isn’t there to begin with.

3.4. Inheritance vs. Composition

A similar debate exists around class inheritance vs. composition.

Just as many people perceive that Shallow Routing offers superior technical flexibility, it’s similarly agreed that you should favor composition over inheritance. However, once again, the domain concept is what really matters. Don’t prioritize technical superiority above all else.

In the diagram above, a Dog is a type of Animal. Inheritance is a natural representation of that. However, an Engine is one of the components that make up a Car, so composition is more appropriate for that relationship.

4. Implementing Documents of a Similar Format

For documents like certificates of income, which may be used overseas, there are two authentication methods: “Apostille” and “Consular legalization.” Consular legalization is more common, while apostille is a simplified process under certain conventions.

In a project I worked on, the goal was to encrypt these documents and verify whether they had been tampered with.

Because the structures and fields of apostille and consular documents appeared similar, an existing system was using a single shared table for both.

4.1. Initial Design

While analyzing the existing system, I suspected that the similarity between apostille and consular documents might just be a coincidence, and that they should not be treated as a single document type. If they were truly the same, the project wouldn’t have been titled “Apostille & Consular Legalization.”

On the other hand, the back-end developer argued there was no need to separate them into two. Ultimately, we compromised by splitting the REST API into two but keeping a single shared table and service.

4.2. Design Change

As the project progressed, the differences between the two documents became more concrete. Apostille and consular documents could have overlapping document numbers, so their numbering systems diverged. Moreover, as service features expanded, their interfaces continued to diverge.

In the end, we decided to separate them completely into two tables and two services. Fortunately, because the external APIs were already split into two, changing the internal structure was relatively easy. Had we tried to avoid refactoring just because splitting them felt like too much trouble, we would have ended up with if-else statements all over the code, opening the gateway to chaos.

4.3. Why did this happen?

In this case, the two documents only seemed alike by coincidence. They were always prone to diverge based on user requirements. The real issue was overlooking the fact that they’re fundamentally different documents—hence having different names in the first place.

Programmers often have a tendency to prioritize implementation convenience. It’s not easy to break that habit. However, you must adhere to the domain concepts rigorously.

5. Storing Encoded Filenames

Suppose a user wants to upload a file named 한글.txt via a web browser.

Because the filename contains special characters, it must be URL-encoded when sent to the server. Likewise, when the file is downloaded, the filename must be URL-encoded again.

So, should the server store the encoded string (%ED%95%9C%EA%B8%80.txt) in the database as is? Or should it decode it back to 한글.txt before storing?

If you store it as 한글.txt, you’ll have to encode it again when sending it back to the user for download. Isn’t it more efficient to just store it as %ED%95%9C%EA%B8%80.txt?

To figure out the essence, consider what the user perceives. They see their file as 한글.txt. They don’t think it’s going to be changed into something else. Therefore, storing it as 한글.txt aligns better with the user’s perspective.

URL encoding is required by ASCII restrictions in certain protocols. It’s not a user requirement. Letting specific technical constraints bleed into other layers is not a good design. That’s why any issues with HTML or protocol limitations should be resolved at that layer, rather than propagating them all the way to the database. The priority should be accurately reflecting the user’s intention, with optimizations considered afterward.

If you only ever needed the download feature, storing the filename as received might be the simplest. But as soon as you add features like listing files or searching by filename, you’ll need the original filename (한글.txt) because that’s what the user understands. If you saved it as %ED%95%9C%EA%B8%80.txt, searching or listing could become problematic.

When you prioritize implementation convenience, even minor changes can throw you off balance. By contrast, if you grasp the essence in your design, you’ll handle unexpected changes much more smoothly.

// Will you display encoded filenames?

%ED%95%9C%EA%B8%80.txt

%0A%0A%ED%85%8C%EC%8A%A4%ED%8A%B8.jpg

%0A%0A%ED%8C%8C%EC%9D%BC.json

// Or will you display original filenames?

한글.txt

테스트.jpg

파일.json

6. Conclusion

From all the examples, a common thread emerges: focusing on why rather than “what.” The what is simply one way to reach the “why.” The purpose (why) rarely changes, but the method (what) can change freely depending on the situation.

Another critical reason to concentrate on why is that, during analysis, you can’t possibly document every single thought the user has. The same goes for the design phase: you can’t capture the designer’s every thought in the design document. The code is the closest thing to fully reflecting those requirements and designs. There will inevitably be gaps, aspects so obvious to the user that they didn’t think to specify them. The problem is that what the user takes for granted can be interpreted entirely differently by the developer.

However, if you keep your mind focused on the why, you end up looking in the same direction, so even if communication has some gaps, the discrepancy won’t be massive. Reducing that gap between the user and the developer is one of the main goals of Essence-Based Interpretation (EBI).

EBI is so fundamental and broad that it’s hard to define its scope or a concrete practice. And it’s not limited to software development.

EBI and Domain-Driven Design (DDD) share the view that you should center on the domain. However, DDD is more systematic and specific, aimed at handling complex or frequently changing domains. On the other hand, EBI is less a strict methodology and more a general mindset that can be applied in various fields, including software. In short, DDD focuses on “figuring out what the requirements are,” whereas EBI emphasizes “understanding why the requirements were defined that way” in the first place.

EBI might sound so obvious that giving it a grand name feels a bit embarrassing. Yet, I hope that clearly naming it as Essence-Based Interpretation helps developers—including myself—recognize its value.

The search for good code brings a shift in how we think and leads us to distill the essence, which in turn prepares us for unpredictable changes. This is a precious challenge unique to software development.