The Ideological Wars of Software Development: Why Do Developers Act This Way?

In the past, just as communism and capitalism were irreconcilable ideologies during the Cold War, there are two contrasting ideologies in the field of software development: principle-focused and pragmatic. Software development is an extremely complex process, and these two ideologies approach problems in fundamentally different ways. Consequently, principle-focused and pragmatic mindsets can significantly affect the success or failure of software projects.

Principle-focused developers believe that development should be grounded in systematic theories of software engineering. They place a strong emphasis on maintainability and argue for meticulous coding from a long-term perspective. Pragmatic developers, on the other hand, focus on solving problems as simply and quickly as possible. Because software is inherently complex, they believe that no matter how carefully you code, it won’t make much difference. Thus, it’s more efficient to react immediately whenever problems arise rather than investing a lot of time upfront.

Most developers fall somewhere between extreme principle-focused and extreme pragmatic mindsets, but this article focuses on these two extremes. We’ll examine their opposing views and approaches, as well as the conflicts that can arise when they collaborate.

1. A Principle-Focused Team Member

1.1. Conflict with a Pragmatic Team Lead

A junior developer, brimming with a desire to learn and grow, is more likely to be principle-focused. Such a developer would be happy under a principle-focused team lead, but in reality, it’s far more common for a principle-focused team member to end up with a pragmatic team lead.

A principle-focused team member in a pragmatic team lead’s environment can feel challenged. They can’t expect much in the way of thorough code reviews, and because the team lead pushes for deadlines, there’s little opportunity to care deeply about code quality. Even if they manage to do some refactoring during lulls, they have to be mindful of the team lead’s reaction.

When problems occur, the principle-focused developer tries to figure out the root cause and address it in the “right” way. However, a pragmatic lead might propose a quick fix that doesn’t bother digging into the root cause. Repetition of this pattern leaves the principle-focused developer feeling frustrated, believing the team lead lacks competence or a sense of responsibility. Since they can’t admire or learn from such a lead, they may show disrespectful behavior or disregard the team lead’s authority. The lead, in turn, senses this and may respond harshly. The principle-focused team member becomes more and more mentally exhausted and eventually resigns. Yet, even at a new company, they’re likely to encounter another pragmatic manager, so this issue tends to persist for the principle-focused developer.

1.2. Projects That Hinder Growth

Because principle-focused developers have a strong desire to grow, they get anxious if the company’s work doesn’t help them learn. This can include maintaining tech-debt-ridden code or even doing new development with outdated or rarely-used technologies.

In such situations, a pragmatic team lead is prone to maintaining the status quo and will likely avoid large-scale refactoring or adopting cutting-edge technologies. Any suggestions from the principle-focused team member will probably be rejected. Just as the first button on a shirt must be correctly fastened, a junior developer’s initial project experience can heavily influence their development trajectory. If it doesn’t feel right, leaving the team might be better in the long run.

However, if the team lead is principle-focused, then waiting might be a good strategy. If the current project is riddled with technical issues, there may eventually be a chance to rebuild it. At that point, the principle-focused team member’s prior maintenance experience provides them with a strong understanding of the domain and requirements—ideal for focusing on technology. Of course, the principle-focused developer must be fully prepared to handle such a major undertaking when the opportunity arises.

1.3. A Word to Principle-Focused Team Members

Here’s what I’d say to a principle-focused team member:

A company is not a school.

You sell your time and expertise in exchange for money. You can’t always do just what you want at a company.

I once moved around between several companies and encountered a few team leads who did respect my ideas, but on two occasions, I ran into extremely pragmatic leads. These pragmatic leads didn’t seem to like having a young, confident team member brimming with enthusiasm. I still believe I tried to respect them as much as possible. When I was in conflict with the team lead, I often asked my colleagues whether I had done something wrong. They would mostly respond, “It’s just that you two don’t get along.”

In retrospect, maybe the pragmatic lead felt uneasy because they feared their own skills were lagging. I, as a principle-focused team member, was openly discussing design patterns and refactoring, which might have worsened their insecurities. To the pragmatic team lead, a confident and somewhat oblivious junior could easily appear irritating.

2. A Principle-Focused Team Lead

If a principle-focused developer’s passion continues, they often become a principle-focused team lead. While I use the term “team lead,” it essentially refers to anyone who takes initiative on a project and exerts significant influence on development.

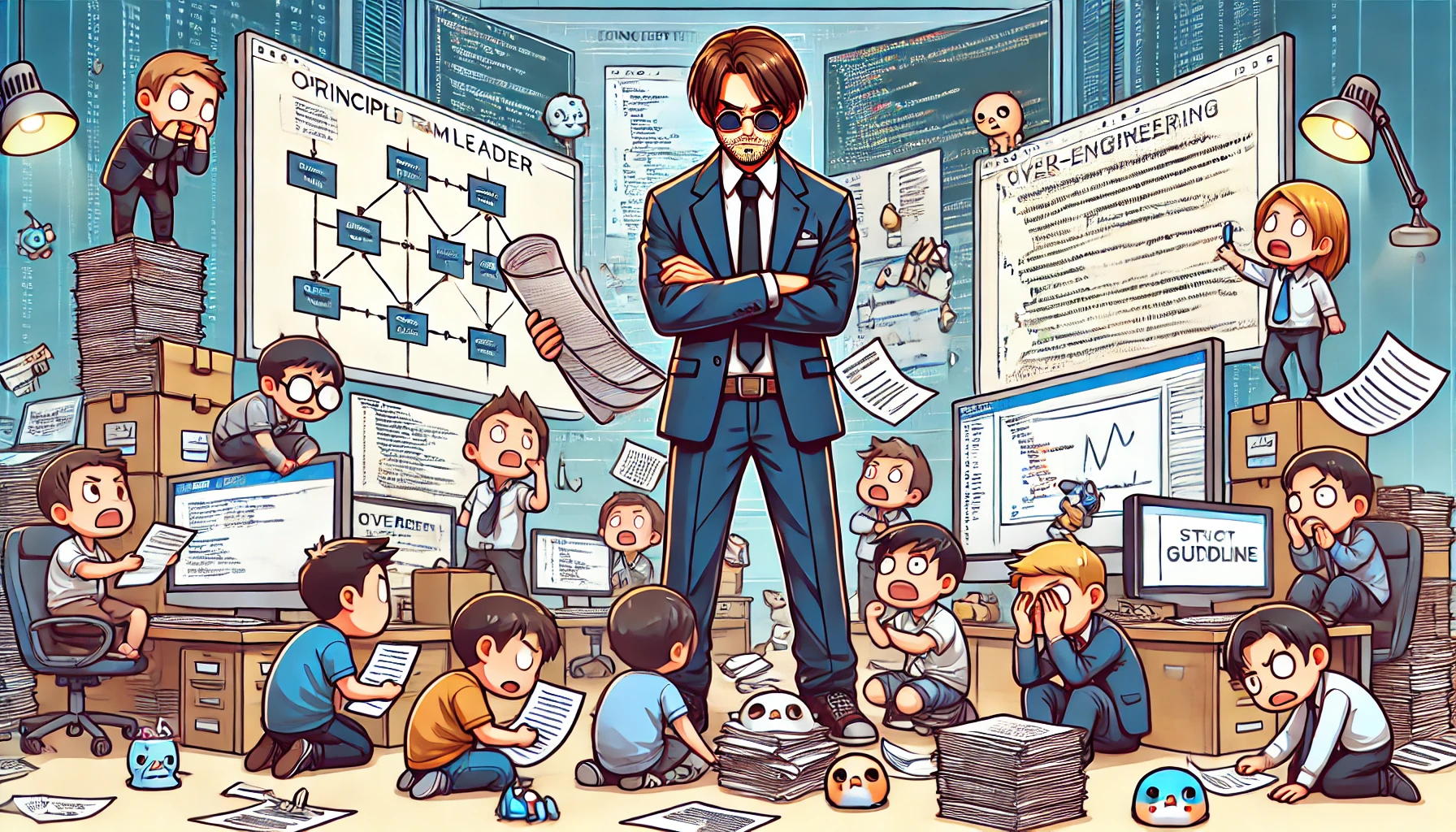

2.1. Over-Engineering

Principle-focused leads can be excessively obsessed with “future-proofing.” This tendency manifests as excessive abstraction and unnecessary application of design patterns—classic forms of over-engineering. Ironically, that can make the code more complex and reduce development efficiency. The very principle of “maintainability” ends up harming maintainability, a tragic outcome indeed.

Over-engineering can frustrate managers because they see the lead working hard on complex design tasks without delivering much visible progress, raising concerns about the schedule. Early in the project, there might be enough leeway to wait and see. But once the manager reaches their limit, they’ll intervene more aggressively.

Additionally, a principle-focused lead who’s deeply invested in future-proofing may have a weaker grasp of the big picture. What happens if a major change in requirements arises mid-project, or a significant technical issue surfaces—something they failed to anticipate while spending so much time on design and research?

The principle-focused lead may see this as someone else’s responsibility—outside the development team’s control—and argue that these changes are an “act of God,” making it logical to extend the deadline or scale back features. But from the manager’s perspective, the question remains: “Why did we spend so much time on design if we can’t adapt quickly to changes?” They might conclude that a pragmatic approach is more helpful in delivering immediate results. Feeling misunderstood, the principle-focused lead grows frustrated because their efforts toward high-quality code seem undervalued.

Part of this is my own story. Whenever I started a new project, I’d set a technical challenge for myself—applying TDD or DDD, for example. How long and how extensively I pursued these experiments depended on the manager’s feedback. Usually, if more than a month passed without much visible product progress, I’d get warned that development was behind schedule.

2.2. Over-Processing

Over-processing involves excessively formal or inefficient development processes. If over-engineering frustrates managers, over-processing frustrates team members. Examples include:

- Requiring overly formal and detailed documentation

- Enforcing overly strict coding rules

- Obsessing over test coverage

A principle-focused lead might demand very high test coverage from the team. While testing is indeed critical, chasing coverage metrics blindly can reduce code flexibility, complicate the test suite, and hamper maintenance.

Team members might initially place high hopes in a principle-focused lead’s grand vision for correct development methodologies. But before long, they may become exhausted by the lead’s overly systematic approach and insistence on detailed plans.

- If the lead’s management is loose, team members may begin ignoring directives bit by bit.

- If the lead’s management is tight, the lead’s own coding time diminishes, and they end up policing every minor mistake. Team members then feel pressured by constant nitpicking, and the lead feels frustrated by their team’s shortcomings.

Sometimes, the demands of a principle-focused lead are so lofty that even the lead themselves finds them hard to meet. Software design is inherently complex and abstract, and it’s tough to fully document your own ideas, let alone expect less-experienced team members to do so without robust guidance. To them, it can be as daunting as writing a book report in grade school.

When I joined a new company as a team lead, I learned that the previous lead, who had been very enthusiastic and principle-driven, demanded 100% code coverage from the team. Sure, maintaining 100% coverage is a great goal. The problem was that the team wrote meticulous tests for every function, so even the smallest changes would break tons of tests.

A function doesn’t typically operate in isolation—it calls other functions and is called by others. Tests must be written at an appropriate granularity for maintainability and productivity, which had apparently been overlooked.

Ultimately, we slashed the test code by 90%, and after that, the team felt more motivated to write practical tests.

2.3. Causes of the Problem

A principle-focused lead is at a stage of maximum trial and error, in part because their authority outweighs their skill and experience. Overconfidence can compound the issue.

There’s often a correlation between enthusiasm and confidence, so a highly motivated principle-focused lead tends to be highly self-assured. That self-assurance may lead them to blame others for problems and to be very forceful about their own methods—a burden for managers and colleagues alike, though the lead themselves often remains oblivious.

A final note to principle-focused leads:

Do not focus on what you want to do, but on what must be done.

Think critically about whether the task at hand is really necessary. Principle-focused leads have a built-in tendency to rationalize what they want to do as if it were strictly required.

3. A Pragmatic Team Member

Where principle-focused developers see company work as a chance to learn and grow, pragmatic developers view it more as a job—an economic activity. So when faced with issues, principle-focused developers tend to put in extra effort to get to the root cause, while pragmatic developers solve the immediate problem with minimal effort.

Pragmatic team members come in various forms:

- Diligent but not passionate about development.

- This type can do tasks that principle-focused members find tedious or burdensome. Their lack of passion for development isn’t necessarily a drawback. They tend to cause fewer complications and can have a smooth career.

- Diligent and passionate about development.

- This can be puzzling at first. If they’re passionate, shouldn’t they be principle-focused? Yet they show little interest in maintainability. Even if you point out issues and offer guidance, they always look for the quickest fix.

- Such developers are often driven not by pure love of software craftsmanship but by job-focused enthusiasm. Their interest in development might be mainly because they need it for their career. For example, they study design patterns or algorithms primarily because those come up in interviews. They rarely delve deeply into such topics unless it’s necessary.

- Lacking passion for the job itself.

- They may be a principle-focused developer who lost motivation due to disillusionment with the company’s direction, or they simply might not care about their work at all.

- If they’re simply doing the bare minimum, conflict with the team lead might be minor. However, the problem is that as they lose motivation, they take less responsibility. For instance, they may make changes without thorough testing, or only carry out tasks exactly as assigned without any proactive problem-solving. Over time, this hurts collaboration and morale.

In general, pragmatic team members find it difficult to grow as developers. They often remain in a company for a long time and become mid-level managers. But without a distinctive advantage, staying in that role indefinitely can be hard. Having seen many regret stepping into management, I urge them to think carefully about the path they truly want.

Here’s what I’d say to a pragmatic team member:

There is no easy or comfortable path. You grow as much as you wrestle with tough problems.

Because pragmatic developers prioritize efficiency, they have fewer opportunities for deep pondering. Yet, whether it’s about technology or human relationships, it’s in the struggle that real growth happens—and with growth comes differentiation.

4. A Pragmatic Team Lead

Many developers become pragmatic team leads. This includes not only those who’ve been pragmatic team members but also those who began as principle-focused leads but eventually turned pragmatic. How can a principle-focused lead transform into a pragmatic lead?

A principle-focused lead might learn about OOP, design patterns, TDD, DDD, MSA, and more, only to find that putting these into practice is no easy feat. These methodologies and architectures all tie together, demanding extensive effort and experience to implement successfully.

For instance, applying MSA (Microservices Architecture) effectively requires a solid understanding of OOP, design patterns, and DDD (Domain-Driven Design). However, many developers never master even OOP and design patterns. TDD also demands a strong foundation in OOP and domain knowledge, plus a flexible design approach.

If a principle-focused lead hasn’t reached that level, trying to apply advanced development methods often creates more problems than it solves. After experiencing several such failures, they may dismiss formal methodologies as unrealistic.

So, from a pragmatic lead’s perspective, principle-focused developers are simply naive—chasing impressive theories that are disconnected from real-world needs. Pragmatic leads see many colleagues preach fancy practices, only to delay project timelines without noticeably improving quality. Therefore, they sometimes view principle-focused developers’ efforts as a waste of time.

Pragmatic leads generally care less about technology and more about analyzing requirements and managing schedules—naturally shifting into a managerial role.

I rarely see pragmatic team leads actively conduct code reviews or provide strong technical guidance. Usually, they assign tasks at the module level and check the final output. If a difficult technical issue arises that a team member can’t solve, the lead might step in. But as the team grows, the lead moves closer to a pure management position.

Another reason pragmatic leads transition fully into management is that development becomes repetitive—without ongoing learning of new technologies or methodologies, every project feels the same. Tired of such repetition, they often prefer management to continuing as a developer.

From my experience, pragmatic leads can yield good results in short-term (under 1 year) SI-type projects. But when a project stretches beyond a year, maintaining quality becomes harder and higher-level managers start to notice issues.

When a pragmatic lead develops an in-house product, they might repeatedly opt to rebuild from scratch rather than continuously improve code. After it grows to a certain level of complexity, they abandon it and start fresh, repeating this cycle every 1–3 years or so.

If the same person maintains a product for years, they might avoid rebuilding, but once that person leaves, maintenance skills drop dramatically, which again leads to rebuilding.

Finally, to pragmatic team leads:

Do not focus on what you can do, but on what must be done.

Sometimes you’ll face elusive bugs requiring extensive research and trial and error. If you only patch them superficially, they’ll likely morph into an even bigger problem later.

5. The Micromanager

A micromanager is a leader who intervenes excessively in how team members carry out their work.

They typically come in two categories:

- A manager who claims to be—or once was—a developer.

- Someone without real development experience but who believes they know enough.

The common trait is that they think they know enough to weigh in on every detail.

Because micromanagers overestimate their own technical abilities, they often share some traits with principle-focused leads—for example, demanding thorough design and documentation. The difference is that, as a manager, their decisions have a broader impact on the entire organization.

A micromanager doesn’t do the coding themselves, so it’s easy for them to pick idealistic or principle-focused approaches. Detached from day-to-day coding realities, they favor what sounds perfect in theory.

I once worked at a security company.

The service quality had been steadily declining, so the manager demanded detailed design documents from every team lead. However, the C++ source code was so huge and tangled—single files exceeding 50k lines—that the code’s structure was already a mess.

It’s normal to do design first and then implement, but the manager demanded we reverse-engineer documentation from already messy code.

After about three weeks, the team gave up trying to produce those design documents. Tragically, the manager believed the team had failed due to lack of skill, rather than realizing the directive itself was misguided.

If the manager felt the team’s capabilities were lacking, the correct approach would have been to hire a more qualified developer rather than impose additional burdens on the existing team.

Managers and team leads have distinct roles. A lead shouldn’t become a pure manager, but equally a manager shouldn’t act like the team lead. When a manager tries to play team lead, the lead can’t exercise their full expertise, and the manager also fails to focus on their own management duties.

Often, managers claim they lead development because of necessity, but in reality, it can be more of a personal preference. If they were prudent, they’d either replace the team lead or adjust the team’s responsibilities.

There’s a saying:

疑人不用 用人不疑(If you doubt a person, do not hire them; if you hire them, do not doubt them).

At a company providing specific data services, the CEO was extremely sharp, and the development team lead was a well-respected developer with both passion and skill.

At first, the CEO was heavily involved in the development process, but it was a startup environment where, even if service outages occurred, they were generally understanding.

A few years later, I revisited and found things had changed dramatically. The original developers were sitting in a separate space with vague tasks, while important work was handled by a new development team under the direct oversight of the CEO. When I asked why, I was told the CEO repeatedly criticized the quality of the old group’s output and eventually decided to lead a new team personally.

This led to another big round of failures. In such a scenario, the CEO should have hired developers who matched his standards rather than trying to manage every detail himself.

6. Conflict Between a Principle-Focused Lead and a Pragmatic Lead

In a project where a principle-focused lead and a pragmatic lead cooperate harmoniously, it often means there’s a bigger external threat: perhaps a demanding client or a high-pressure micromanager overshadowing any internal disagreements.

Otherwise, whenever the two leads must collaborate (e.g., on API design), they’ll clash over almost every decision.

6.1. The Principle-Focused Lead’s View

The principle-focused lead feels held back by the pragmatic lead.

- In API design, the pragmatic lead wants minimal changes to their own code, so the resulting API is less intuitive, harder to understand, and forces more work on the principle-focused lead.

- As the project evolves, new APIs might be needed. But if the existing API can be adapted—even if awkwardly—the pragmatic lead will push to reuse it.

- This reinforces the principle-focused lead’s belief that the pragmatic lead only cares about their immediate convenience, lacks vision, and generally lacks skill.

- The principle-focused lead worries that continually deferring to the pragmatic lead’s approach will cause severe problems eventually.

- They also notice the system is aging and has structural issues, but the pragmatic lead keeps rejecting large-scale refactoring plans.

- This simplistic development strategy doesn’t help the principle-focused lead grow as a developer.

6.2. The Pragmatic Lead’s View

The pragmatic lead thinks the principle-focused lead unnecessarily complicates the project.

- The principle-focused lead introduces technologies they themselves haven’t fully mastered, making the system overly complex.

- They fixate on personal growth, neglecting project deadlines or success.

- The two may have agreed on an API, yet the principle-focused lead keeps requesting small changes. Their obsession with details slows progress.

- Refactoring or rewriting from scratch doesn’t guarantee real improvement; it just threatens schedules.

6.3. The Micromanager as Mediator

The micromanager believes they can hear both sides and make logical decisions.

They aim to be fair and objective, but in reality, the principle-focused lead starts at a disadvantage. Suggesting change or introducing new methods is always harder to justify than doing nothing. The principle-focused lead typically has to articulate a lengthy argument, referencing theory to persuade the micromanager.

By contrast, the pragmatic lead can simply ask, “But why do we need to change it?”—an easy position to defend. Even a knowledgeable principle-focused lead struggles with repeated “Why?” questions, especially since they must also persuade a micromanager who might lack technical depth. It becomes a 2-on-1 situation.

Even if the principle-focused lead has some theoretical background, it might not carry much weight when explaining to a micromanager who only has a vague sense of feasibility. Ultimately, the micromanager’s goal of making a purely logical judgment often gives way to recommending a compromise that accounts for both parties’ feelings.

Over time, the micromanager may side more with the pragmatic lead. The pragmatic approach is easier to understand and delivers quick, visible outcomes.

Or the micromanager might drop mediation, instructing both leads to “work it out.” This is the worst outcome. With no final arbiter, the conflict intensifies, and the project risks failing altogether.

6.4. Possible Solutions

Ultimately, the situation of two leads butting heads often stems from the micromanager themselves. Perhaps the manager holds final decision-making authority, imagining they can moderate the two leads while also wanting to retain control of development.

A truly senior tech lead with vast experience could mediate effectively, but that would require the senior tech lead to oversee the project and lead the team leads. Usually, there isn’t a more seasoned, higher-level tech lead the team leads can trust.

When no senior tech lead exists, having the manager personally mediate is difficult. Favoring one side alienates the other. In the long run, it’s best to assign clear authority and responsibility to one lead, accepting the associated risks. If it’s a short-term external contract project, a pragmatic lead might be best. If it’s a long-term internal product needing continuous improvement, a principle-focused lead might be more appropriate. Hiring developers thoughtlessly can create “technical debt” in the team itself, making it unmanageable over time.

I worked at a company headquartered in Europe, developing a large online service. Multiple development teams all contributed to the same product, alongside a dedicated QA team. Notably, there was an Architecture (Architect) team, including a chief architect at the top.

Because design, implementation, and testing were all separated, design discussions happened before coding. Architects, dev teams, and QA teams would meet to discuss design details and testing approaches.

All interface and design decisions came from the architects, so it was rare for two dev teams to clash. A development lead might disagree with the architects’ decisions, but the architects held ultimate authority and responsibility for design. Therefore, it never escalated into a major issue.

7. Conclusion

The clash isn’t truly caused by principle-focused vs. pragmatic approaches. Even if two people have different ideologies, trust and mutual respect can lead to a smooth project.

What causes conflict is human emotion and personal ambition. Once their interests diverge, the ideological gap just magnifies the rift.

From the manager’s viewpoint, pragmatic developers’ arguments can seem very appealing. Still, one must think carefully about what happens if a company continues with purely pragmatic development for years.

A principle-focused approach doesn’t yield immediate results; it also involves strong opinions and sometimes leads to costly over-engineering. If the company can’t handle that trial and error, it may drift toward a purely pragmatic approach, ultimately leaving only pragmatic developers. Hiring a principle-focused developer into that environment later on won’t fix anything—the existing pragmatic leads will push back.

Conversely, if principle-focused developers dominate, they may focus more on research or experimental technologies, causing productivity to plummet. Since they don’t fully grasp every facet of advanced development theory, software quality might not improve that much anyway.

A manager who values software quality sees the potential in principle-focused developers’ trial and error. However, their growth can be slower than expected.

To address these issues, at least one competent senior technical leader is needed. Such a leader can reduce principle-focused developers’ missteps and utilize pragmatic developers effectively.

Without that senior leader, a company must select developers based on the nature of the product. For in-house products needing ongoing improvement, minimize hiring too many pragmatists. For short-term outsourcing, do the opposite and minimize principle-focused developers. Just like technical debt piles up and hinders maintainability, recklessly hiring the wrong people for expediency can create “hiring debt” that endangers the development organization’s stability.